Launched in Cape Town in 2017, Mami Wata is a clothing brand that combines a powerful graphic aesthetic with a commitment to investing in local production and communities. The name – West African pidgin for water spirit – reflects Mami Wata’s roots in Cape Town’s surf culture, which is not a western import, but a sport that can be traced back to at least 1640 in what is now Ghana and is better understood as the revival of an ancient practice. Mami Wata aims to use African-grown cotton, and its products range from an R800 rand T shirt – about £32 – to a £500 medium-length surfboard. The brand describes the simple graphic design that decorates the board as inspired by the patterns found on walls built in Ndebele communities, which relate to tribal identity. According to its site, “many consider these designs to be modernist but in actual fact they predate modernism by many thousands of years”.

Mami Wata was started by Andy Davis, Nick Dutton and Peet Pienaar, who recruited Selema Masekela, the American-born son of the famous SouthAfrican jazz musician Hugh Masekela, as an investor and collaborator. Selema Masekela is a filmmaker, sports reporter and producer who encouraged Mami Wata to publish its first book, AFROSURF, which celebrated the energy and optimism of African surfing. It has been followed by a second book, AFROSPORT, which takes a wider view. Through the lens of sport, the new book presents a powerful celebration of Africa’s distinctive contribution to design and culture.

“The world in general knows very little about Africa and why certain things look the way they do,” says Mami Wata’s creative director Peet Pienaar. “Western designers think that everything that happens in Africa is vernacular and that African designers are behind in some way. Western design isn’t the default.”

As a discipline, African design is rooted in centuries-old traditions and a style that encompasses a broad range of techniques, reflecting the cultural, historical and socioeconomic contexts of its diverse regions. From ornate cave paintings in South Africa’s Cederberg Mountains to masks produced by cultures across the continent, its histories are as varied as its communities. For centuries, fractals have been used in Africa as a design tool across sculpture, architecture and pattern making, even in the creation of sports jerseys and uniforms. In 2018, South African researchers confidently dated the criss-cross patterns they found on a fragment of rock in the Blombos Cave as having been carved an unimaginable 77,000 years ago. They interpreted them as representing the earliest-known example of abstraction used as a form of graphic communication. Despite these ground-breaking innovations, African design has been marginalised within the global discourse. AFROSPORT isn’t going to change all that on its own, but it makes a strong case.

“A lot of design schools are pushing African designers to become western designers because that’s the default,” Pienaar says. “When African designers start including cultural elements into their designs, it’s immediately seen as vernacular. All of us who are culturally ethnic are excluded.” Without knowledge and awareness of its history, this perpetuates the stereotype that African design is only synonymous with animal prints and Sahara aesthetics. Whereas, in reality, it is a dynamic and playful discipline that’s rooted in connectivity and a shared post-colonial mindset. AFROSPORT is more than just a celebration of African design and sports culture – it's a call to action by placing Africa at the centre. “The world is going to be influenced by Africa,”says Pienaar. “It's very important that people start being more aware of what's happening. It's time that we read more about Africa.”

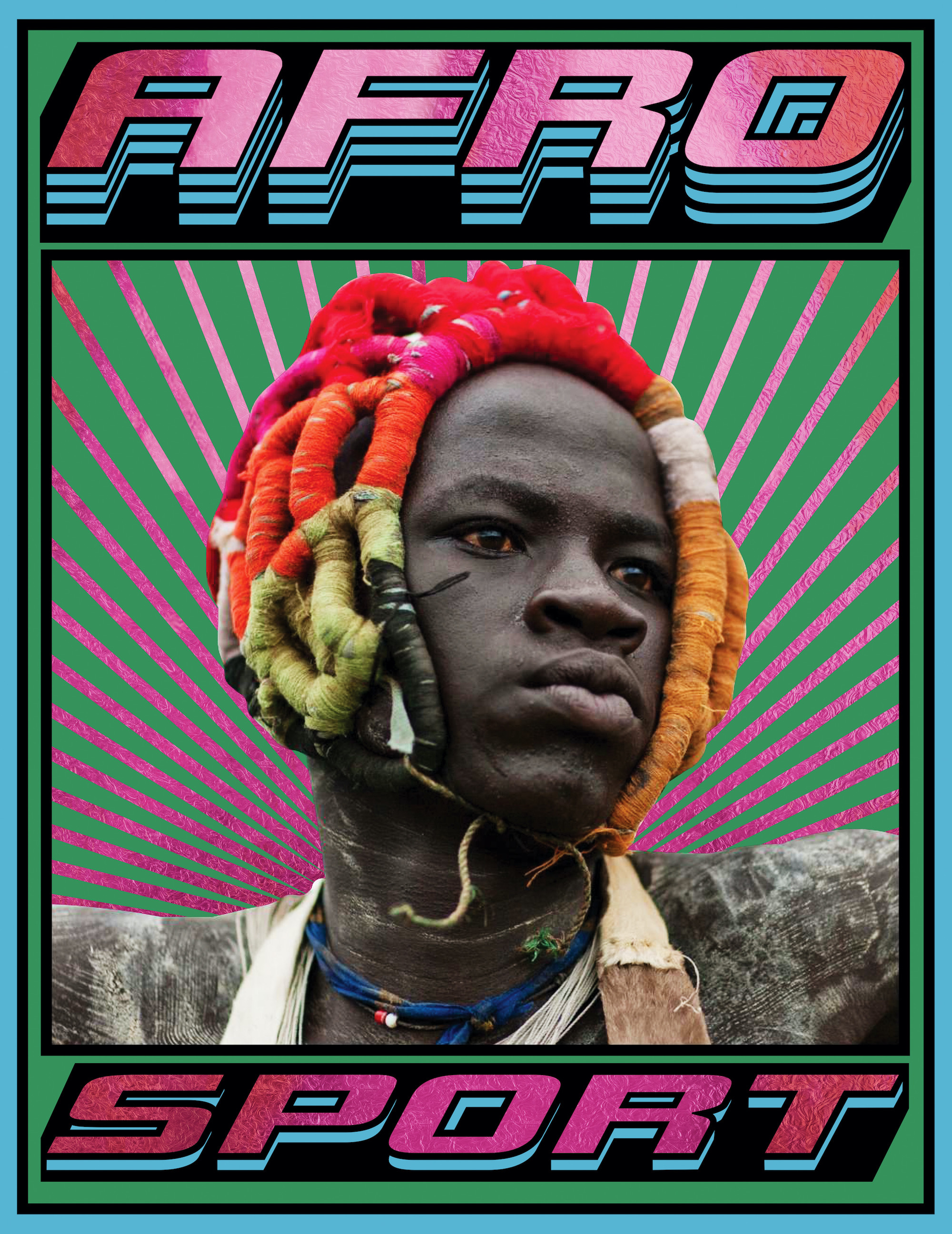

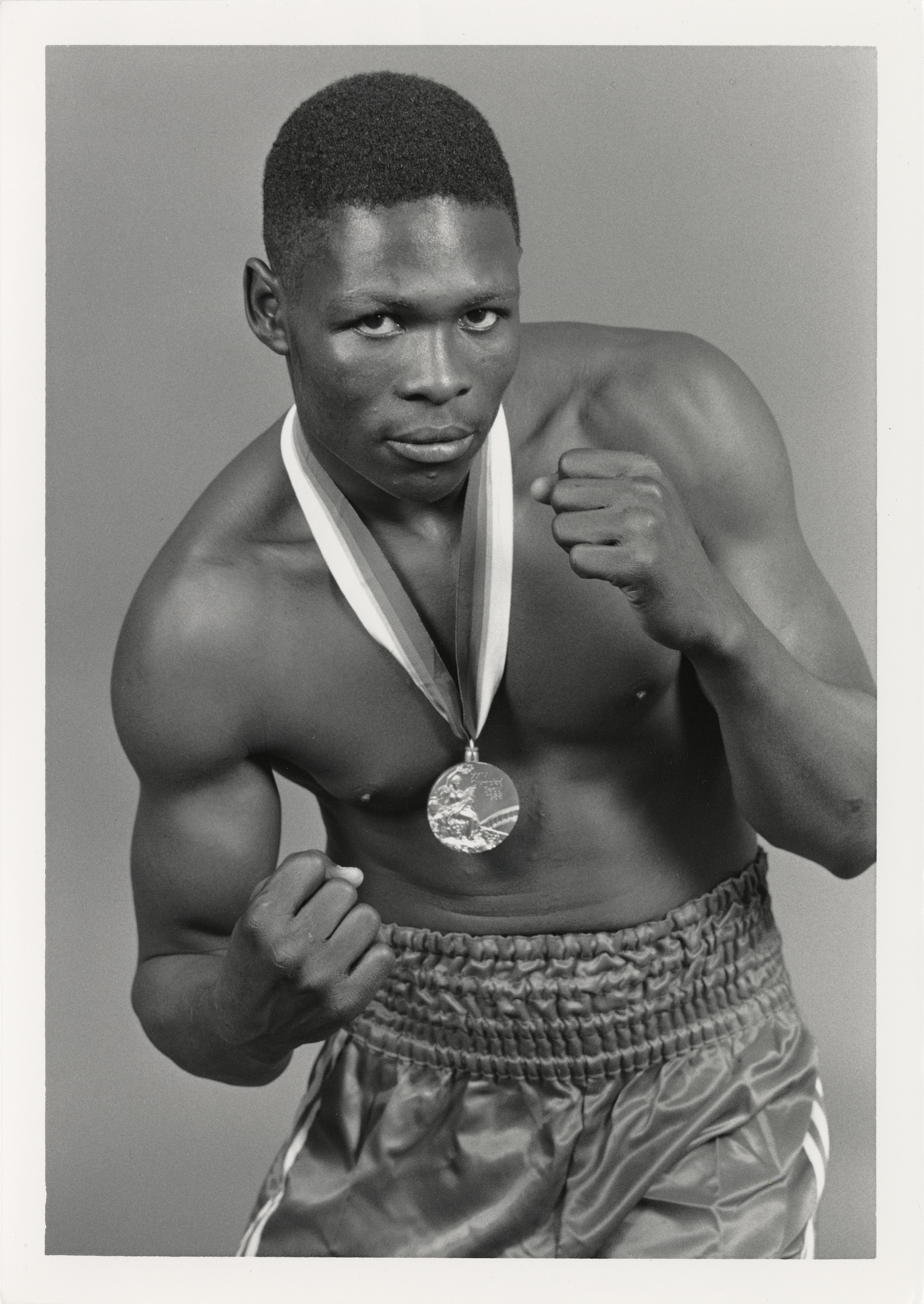

With its deliciously iridescent coruscating graphic cover, fuelled by reflective pinks and almost-lilac blues, the book takes a seductive rather than a didactic approach. A thick, boxy border directs the eye to a striking photograph taken 14 years ago by Eric Lafforgue. In perfect central alignment, the subject’s head is protected by a helmet of woven knots, his lips pursed as his eyes fire off into the distance. He’s in the midst of a game of donga, a stick fighting sport hailing from Ethiopia. Inside the book, Robert Wangila, a professional boxer from Kenya, raises his fists as he poses triumphantly for the camera (the photographer remains unknown). Wangila won a gold medal at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul. His pendant hangs proudly around his neck, decorated by Giuseppe Cassioli’s portrayal of Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. She holds a winner’s crown and palm in her hands, while the Colosseum is depicted in the background – the top right corner is where the name of the host city and Games numeral sits.

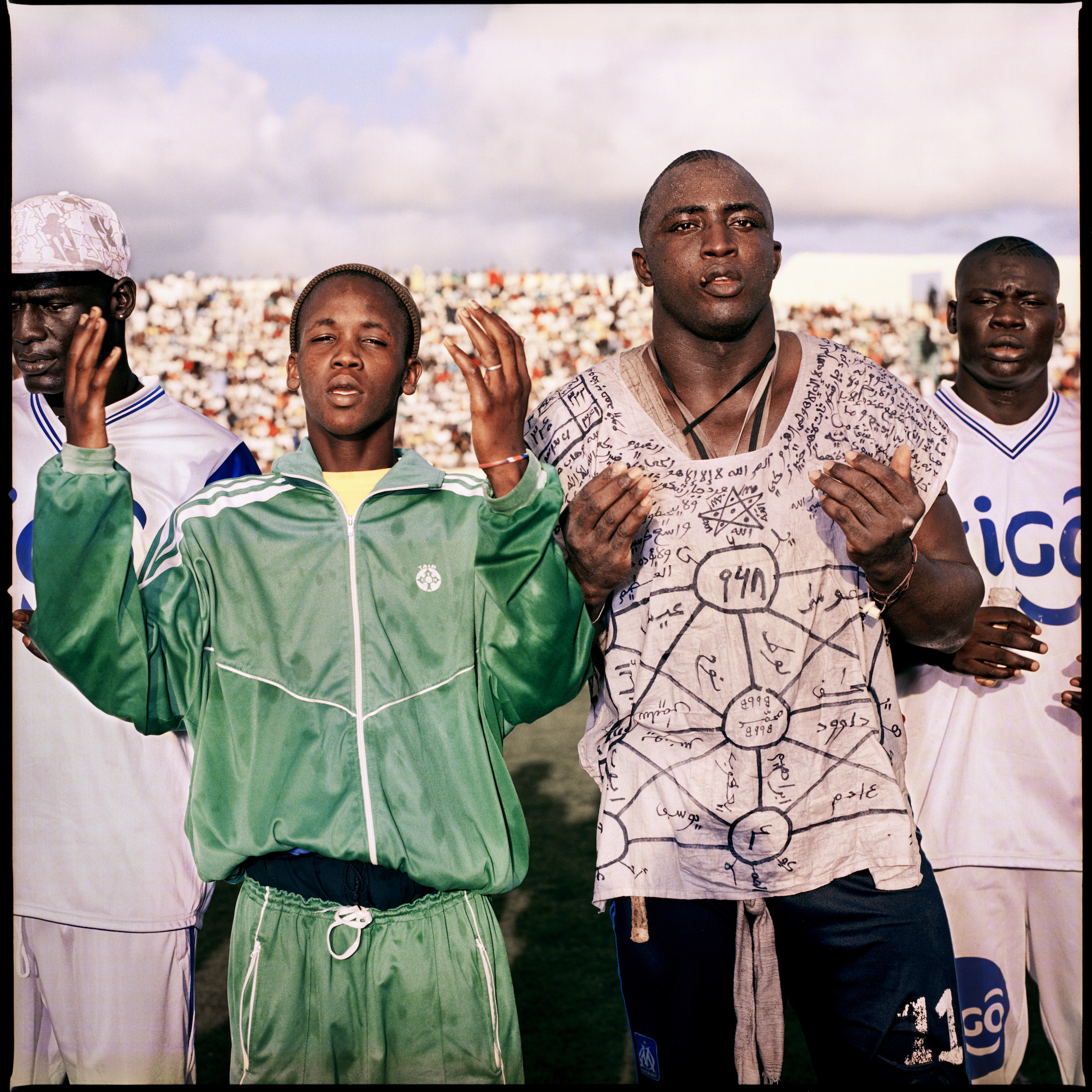

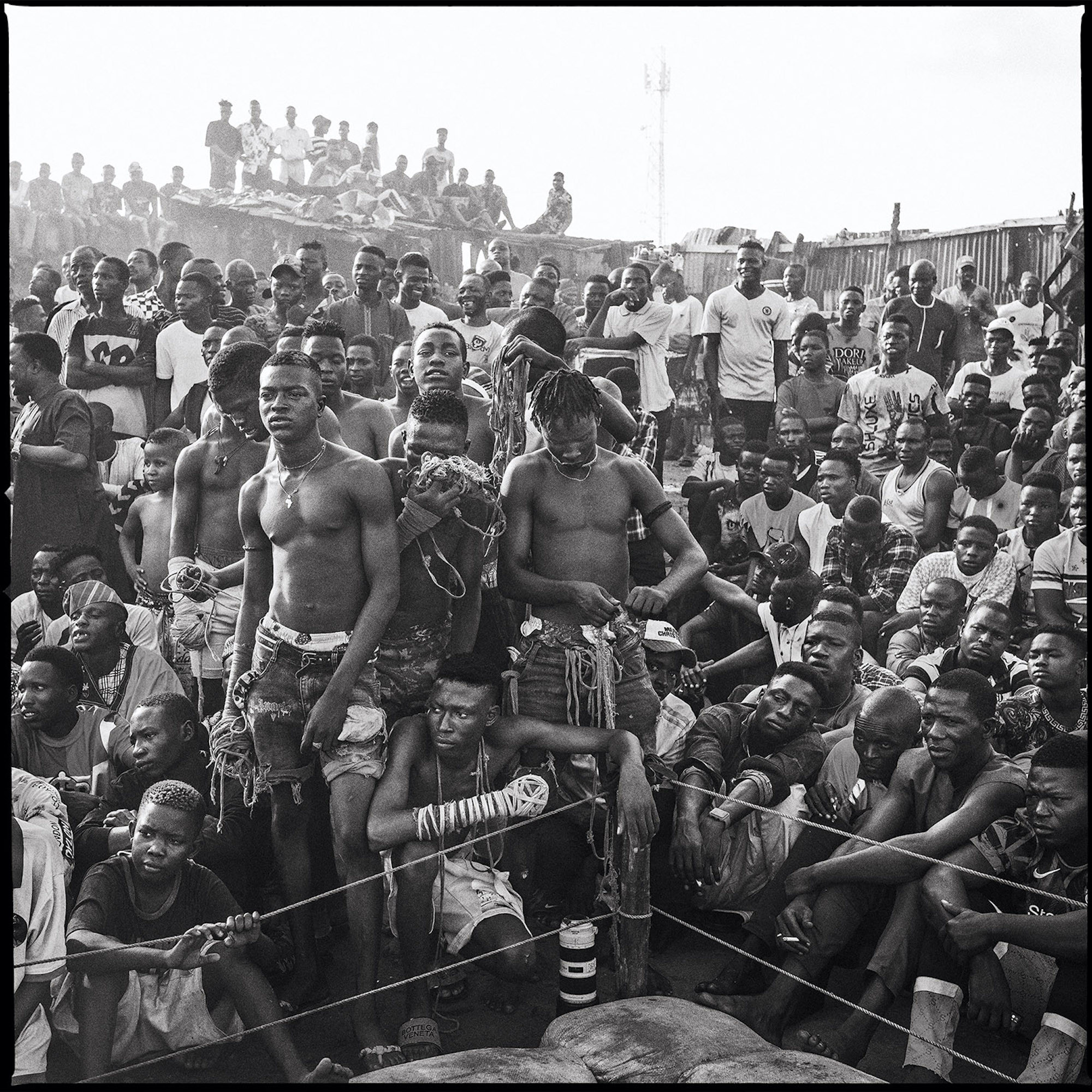

The relationship between sport and design has long been dynamic and mutually reinforcing, driving culture, economy and social development. Its role is highlighted through AFROSPORT’s 150 photographs from image-makers such as Pieter Hugo, Nana Yaw Oduro and Kyle Weeks. It documents significant events including the Rugby World Cup Trophy Tour in Cape Town last year, and the moment that the Senegalese football team won the Africa Cup of Nations for the first time in 2022. In a bustling, smoky image, the team are portrayed raising their trophy in a gesture of victory in the crowded streets of Dakar. The book highlights sports from boxing to motorbike racing, as well as some that are more traditional or less well known. This includes dambe fighting, a martial art from the Hausa people of Nigeria, and laamb wrestling, a Senegalese fusion of traditional wrestling styles that has overtaken football in popularity. Contributions from writers, artists, skate brands, filmmakers and sports figures including Joakim Noah, Didier Drogba and Gerard Akindes each offer their perspective on how sport and design has played an influential role in their lives, and the development of Africa

Casting a wide net from the past to the presentday, AFROSPORT portrays Africa’s identity amidst a shifting societal landscape. Driven by the continent’s rapid growth in population, the so-called youthquake that has given Africa the largest percentage of people under the age of 25 in the world, a new visual language is emerging. Demographic change is both a challenge in its effect on unemployment rates, access to education and healthcare, and an opportunity. A youthful Africa offers a vast pool of creativity and innovation. If effectively tapped into, it has the potential to drive economic growth, placing the younger generation at the front of visual culture. At the same time, globalisation and the instant communication of social media has sparked a new kind of interaction between the West and the Global South. Football is inescapable. In CapeTown and Johannesburg, people wear Chelsea jerseys embellished with the symbols of western consumerism, which have been co-opted into everyday clothing. Traditional sports, such as donga, are attracting more attention and sporting talents no longer need to leave their homes to start a career. African culture has assimilated western influences, and the line between the two has eroded. The colonial powers had originally introduced European sports as part of their supposed civilising mission and saw them appropriated by their unwilling subjects. Something similar is happening now. “There's a strong new language in Africa that's happening now, and it’s completely mixed up with western culture,” says Pienaar. “A lot of people think that African designers use symbols as appropriation or as aspiration. But the Nike logo, for example, holds a completely different meaning, since it isn't available in most African countries. People start seeing the symbol appear on jerseys and at football matches, but they don’t associate it with the product. There’s a new language developing.”

It could also be said that Africa’s unique visual language – one that exudes a sense of boldness, storytelling and shared values – matured once the continent became independent in the 60s. Theodosia Salome Okoh, a Ghanaian teacher, artist and hockey player, designed Ghana’s national flag in1957 with three colours – green, yellow and red – plus a black star. The latter is identified as a symbol for the emancipation of Africa, adopted first from the flag of Black Star Line, a shipping line established by Marcus Garvey which ran from 1919 to 1922. When other former colonies became independent, they opted for the same colour palette in solidarity.The design ethos of AFROSPORT embodies this spirit, characterised by bold colour palettes and a non-linear approach to layout and composition. It avoids formal grid layouts in favour of organic, free-flowing aesthetics, nodding to the lively nature of the design language. This becomes evident throughout the graphics, designed by Pienaar and the Mami Wata team, and in the stories that unfold throughout the pages. One such example is that of The Orlando Pirates, a football team based in Soweto, Orlando. Formerly known as the Orlando Boys Club, the teenagers who originally formed the club in 1984 eventually broke away to join Andries ‘Pele Pele’ Mkhwanazi, a boxing instructor who encouraged the genesis of a new football club in 1987, dubbing them ‘amapirate’, which means ‘pirates’ in isiZulu. The team took a name that had been intended as an insult, and created a logo and identity that resonated with their defiance – a monochromatic skull and crossbones. It refers back to the buccaneering days of Caribbean piracy, but also to the iconography of contemporary American football. Pienaar finishes, “there’s an incredible playfulness in African design, especially in sport.”

AFROSPORT can be purchased here

This feature appeared in Issue 2 of Anima, head here to purchase a copy or subscribe