Norman Foster is an architect who is anything but a Luddite about digital technology. His studio uses fly throughs, and puts Unreal Engine, the programme developed by Epic Games, to work to create outdoor 1:1 virtual reality delivered with headsets and backpacks. But he is unhappy about at least one unintended consequence of technological change. “Computer drawings are so misleading that it drives me to despair. We have become so accustomed to seductive, treacly renderings that we lose sight of what drawings can tell us. I always ask the guys in the office to get back to basics, to make the ‘wire’ drawings that computers once did without difficulty, which can be helpful in understanding a design.”

Foster, a gifted draughtsman himself, played a significant role in the last days of a tradition of architectural rendering many centuries old that the digital explosion has finally ended. Rendering has been many things: a design tool, a set of instructions for builders, and sometimes an element in a marketing campaign. It represents a fascinating mix of art, skill and process. The raw material that architectural renderers worked with were the plans and cross sections that architects use to design their buildings, but which to most people are as far removed from experiencing architecture as sheet music is from listening to an orchestra play it.

Rendering has been compared with literary translation and is a special skill that demands the ability to represent something that exists only in the mind of the architect, and which may one day need to be judged against the physical reality of a completed building. It is a tradition that takes in Michelangelo’s drawings for his own design for St Peter’s Basilica in Rome and Joseph Gandy’s paintings of John Soane’s design for the Bank of England in London.

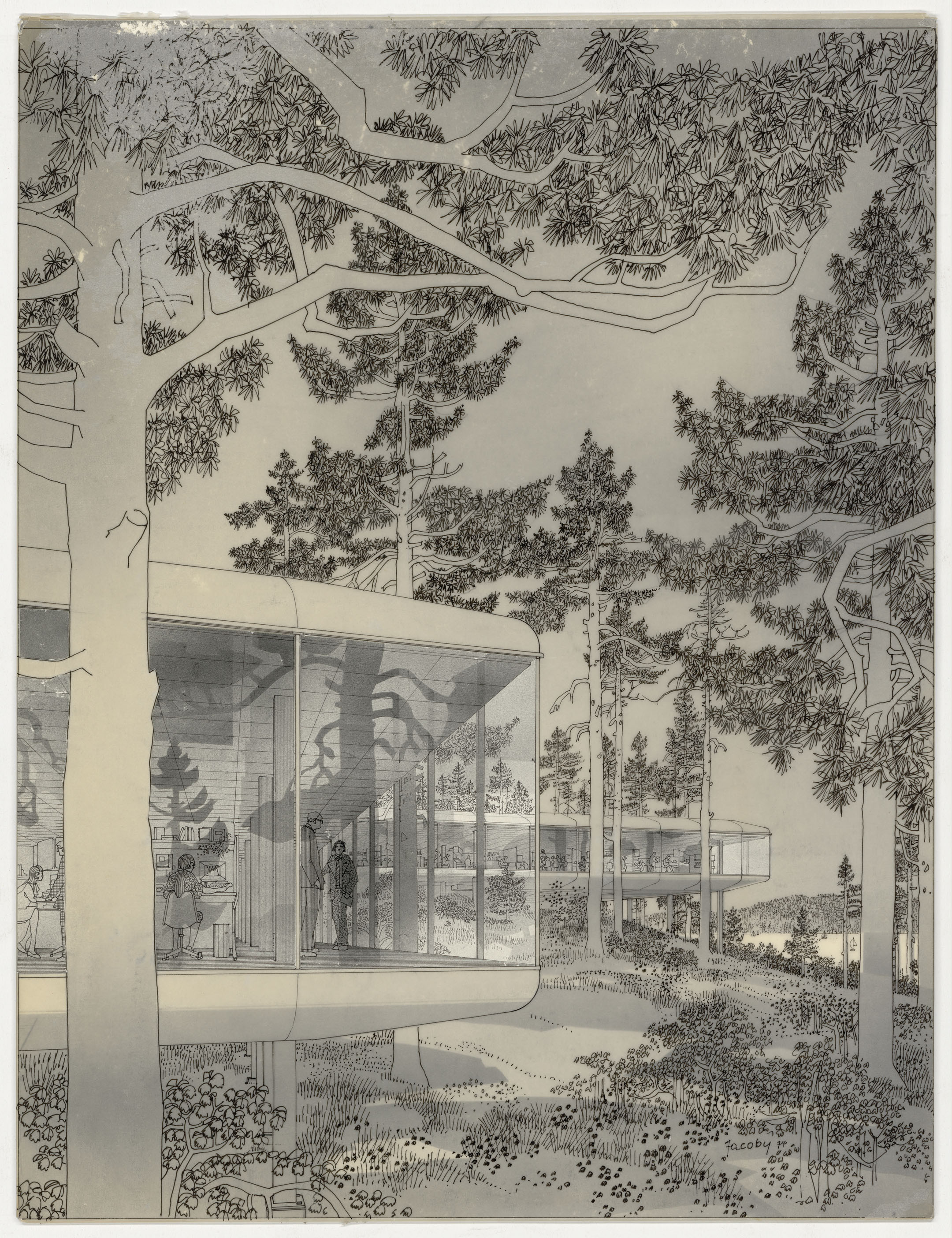

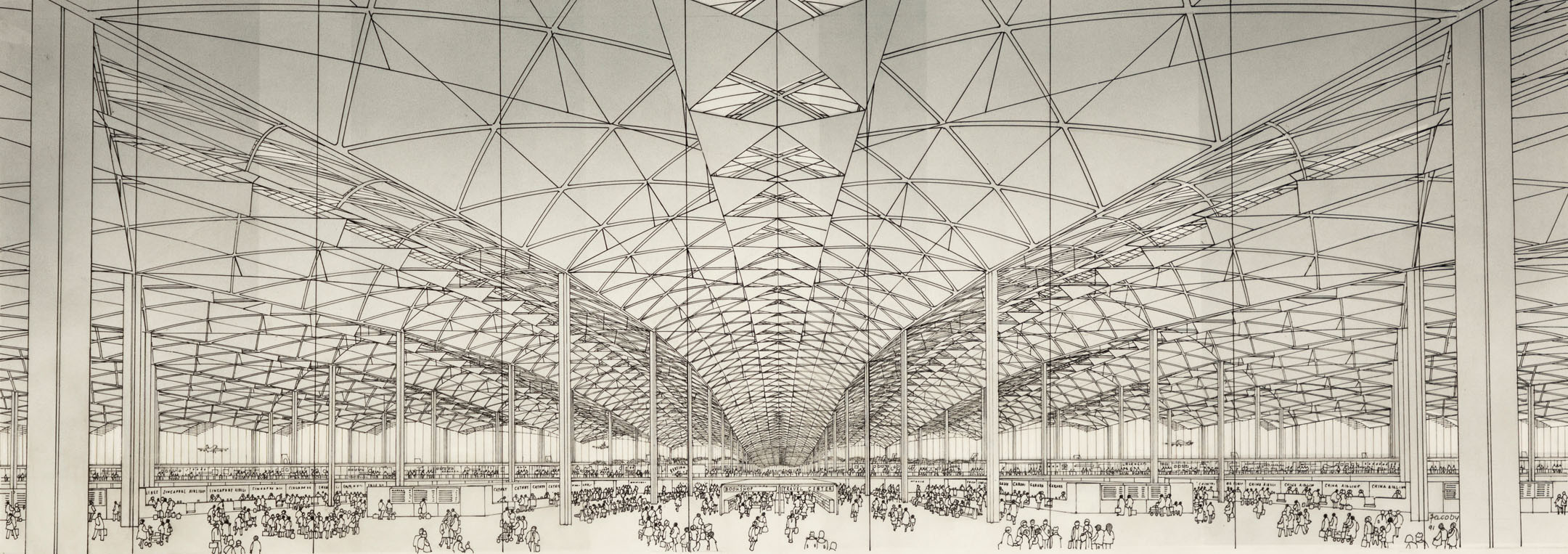

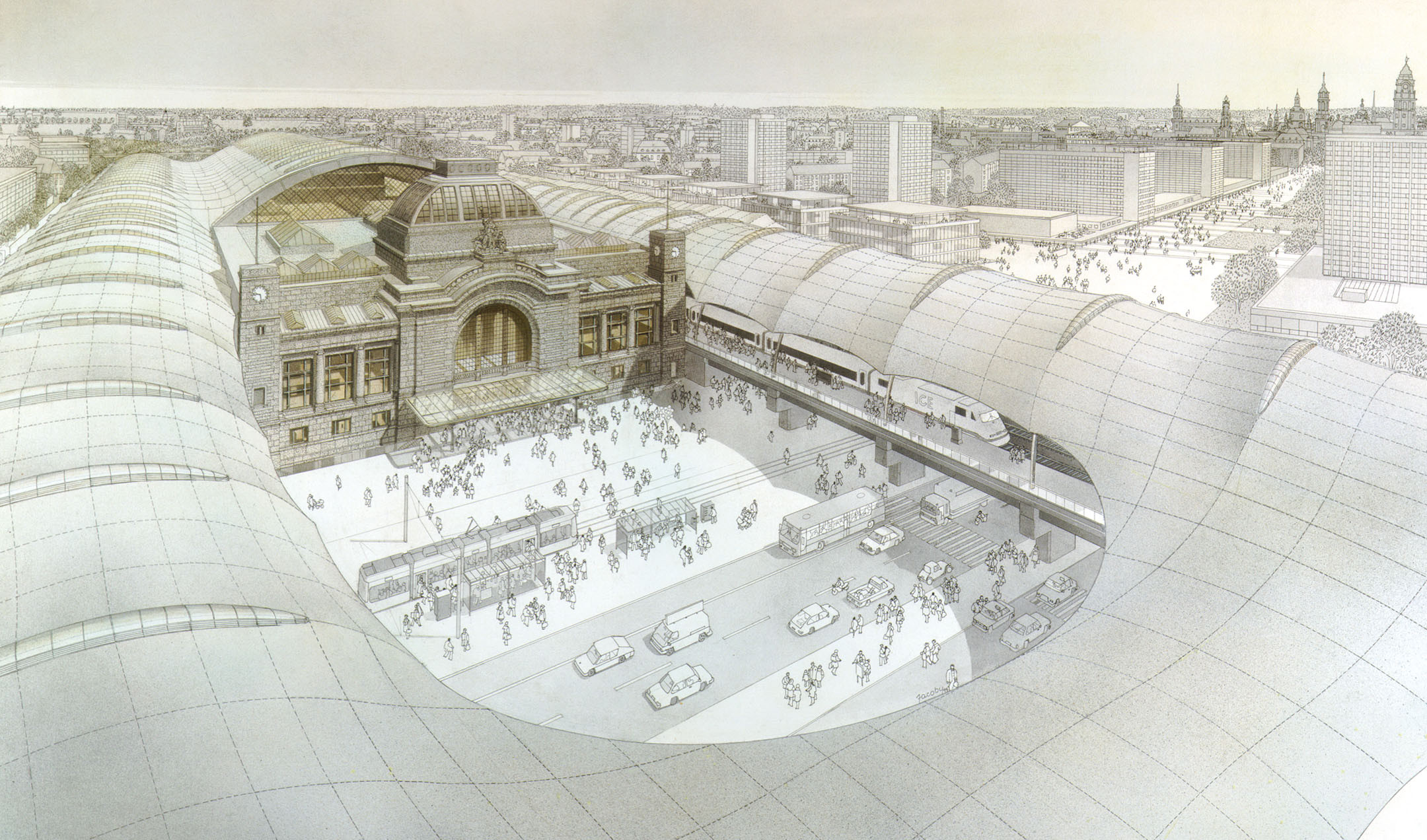

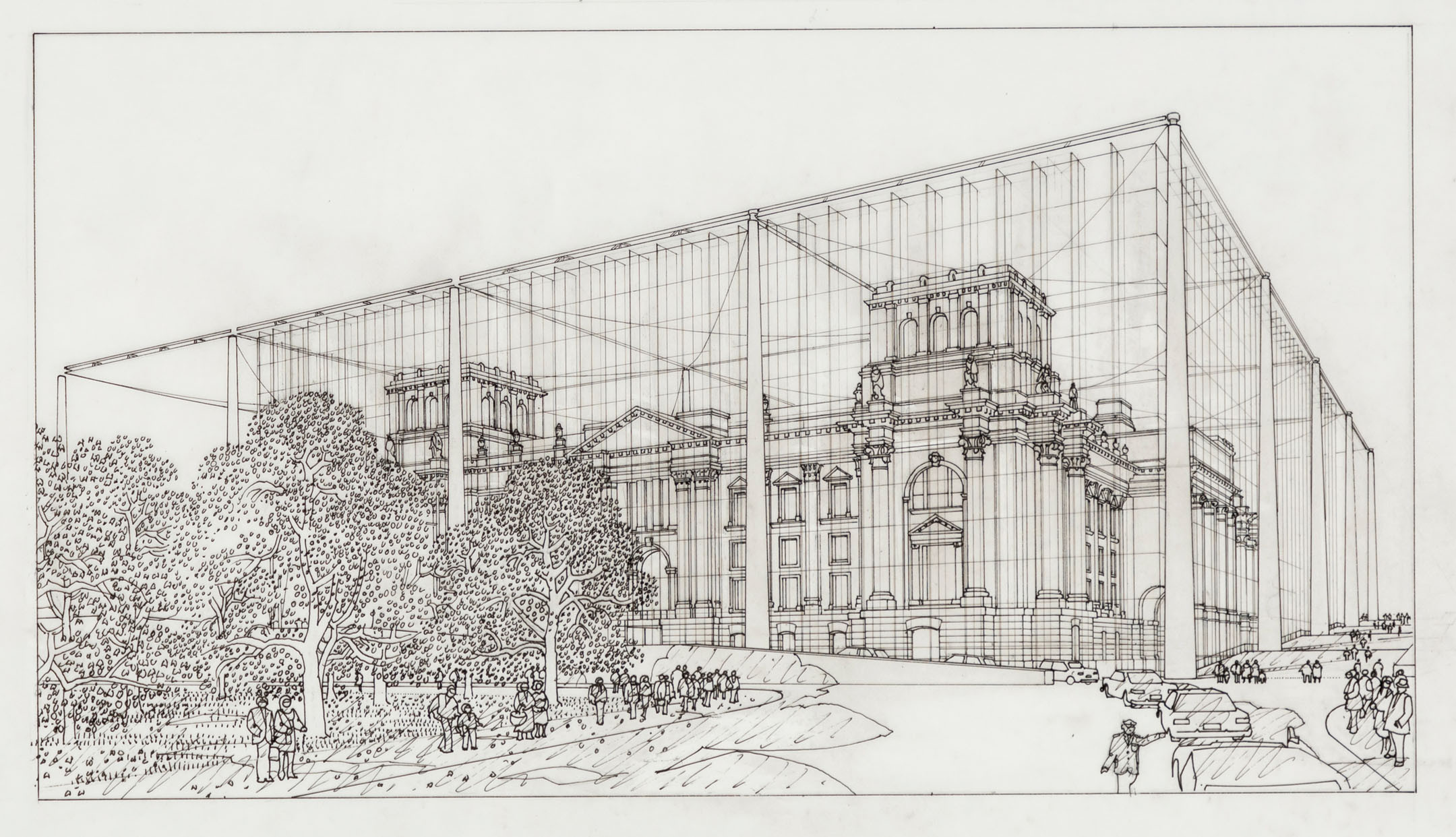

For almost 30 years Foster worked closely with Helmut Jacoby, who died aged 79 in 2005 and was perhaps the last, and certainly one of the most gifted and consistent of architectural draughtsmen. Jacoby spanned the transition from the drawing board to the computer workstation, although he limited himself to ink on paper. He worked for Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius in the 1960s and after 1971, with Foster. "I do interpretations. I interpret thoughts, I interpret two-dimensional drawings into a three-dimensional one, I interpret intentions," Jacoby told one interviewer. For Foster the appeal of Jacoby was that he was a truth teller, rather than a flatterer.

Jacoby was born in 1926 in Halle, a city that by the time he moved to Berlin to study engineering had become part of East Germany. He switched to an architecture course in Stuttgart after a year, then moved to New York in 1950 where he worked as an architectural assistant in a couple of large firms while completing his architectural education at Harvard. He discovered that his talent was to represent and explore other architects’ ideas, rather than design buildings himself, and he started his own consultancy in New York in 1956. Jacoby’s arrival in New York coincided with a generational shift in architecture. The late flowering of the Art Deco of the Rockefeller Center era, drawn by Hugh Ferris and designed by Wallace Harrison, was giving way to mid-century modernity, and Jacoby’s extraordinarily precise and consistent drawings quickly became its embodiment. “Hugh Ferris could get away with drawing fuzzy outlines. But you cannot draw Mies van der Rohe’s architecture fuzzily,” Jacoby told his American contemporary, the architectural draughtsman Frank Costantino.

Jacoby’s work helped the young I.M. Pei start his independent career by winning the competition to design the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse in 1960. He drew for Eero Saarinen, and then for Philip Johnson. He delineated Johnson’s design for the Pre-Columbian gallery at Dumbarton Oaks in 1960 in Washington, as well as his work for the Lincoln Center in New York. “Johnson was the person who discovered me, who made me, [he]…was a decisive factor for the success of my career,” Jacoby once suggested.

Jacoby believed in precision and had an extraordinarily painstaking and time-consuming working method that demanded going over and over the drawing with a needle-nibbed pen to create a delicate mesh of fine lines suggesting shade and volume. He told Costantino that “effort is essential.” His approach was always to be ready to “try again; to do a drawing five times; maybe the second one will be better.”

He always used an extremely restricted palette. There might be occasional touches of colour, applied sparingly with an air brush, but unless it was carefully controlled, he worried that it could take over from the architectural subject of the drawing.

He told Constantino that “the sky can be up to 50 per cent of a drawing and it competes with the building.” Keeping things as monochrome as possible also made for a stronger representation of form.

For 10 years Jacoby worked with every major architect in America. On one important architectural commission he was working simultaneously for three different practices in competition with each other. The work was always perfection, but it took its toll on Jacoby’s health. By 1968 he was exhausted and disillusioned. The first tremors of postmodernism were in the air. It was not a style for which Jacoby had much sympathy, and it made his own work seem passé for a while. He closed his office, went travelling, and then moved back to Germany.

Even when he was still a little-known young architect specialising in industrial buildings because everything else was already spoken for, Foster wanted to work with the most interesting people that he could find. He met Buckminster Fuller in 1970 and supported him on a plan for a theatre beneath the quadrangle of an Oxford college. “I was pursuing the best of every kind,” Foster remembers. “Otl Aicher was the best graphic designer. Jacoby was the absolute pinnacle as a delineator. I tracked him down, to my surprise he was in Germany. I went to see him, and we had dinner at his home. In his own words he told me he had burned out. He jumped at the opportunity, beyond being interested in the projects we had, he said he was grateful that I brought him back to working.”

It was the start of a new stage of Jacoby’s career. He did a whole series of drawings for Derek Walker, the chief architect of the new town of Milton Keynes, and for a range of Foster’s buildings, some built such as the Willis Faber offices in Ipswich, and the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, others not, from a planned apartment tower in New York adjacent to Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum to the redevelopment of the centre of Hammersmith.

“He would get the clinical base data from us,” notes Foster, “the cross sections and plans. I could set up a three-point perspective and would do a sketch for him. He prepared what you might call a cartoon, a rough. We bounced back with drawings, we always dealt one to one.”

“Helmut was less atmospheric than Birkin Hayward, who I also worked with, he was closer to reality. He had a very personal style, he abbreviated trees, skies, water. It was a quest for truth in portrayal, an exploration of what it will be like. You don’t want to be seduced; you want somebody to tell you the truth. Some offices use illustrators only for presentations to clients. For me it was never primarily something for a client. I was using Helmut as a sounding board. He gives you pause, or validation. Some people can always make it look better than it really is. Helmut always drew it as it was. When Helmut showed you his drawing, it was ‘Wow we got it right’, or ‘Oh My God…’. He was always accurate.”

The exhibition ‘Norman Foster’ runs at the Centre Pompidou in Paris from May 10th to August 7th, 2023