I always carry a handkerchief.

I can think of few more useful or functional products that have evolved over decades to become so beautiful and distinct, while remaining so essential and simple. Over the years I have collected and been given dozens and dozens of cotton squares. I have drawers full of colourful, neatly folded handkerchiefs that are unfailingly cheerful.

There are not many items I own that survive daily use for so many years. While they see blood, sweat and tears, it is rare I throw one away — far more common is producing a fresh and clean handkerchief for a friend who was caught unprepared in a moment of need. I love that it will never be returned but will become their own.

Almost everything I have designed has been done sitting in a Supporto. I have been a fan since the late ’80s. I have them at home, had them at Apple, and now, we have them at my design firm LoveFrom.

I struggle with most task chairs. They seem rather patronising to me, appearing so absurdly complex as if designed to satisfy the most extraordinary requirements.

Supporto is different. It is rational, sophisticated and refined. It gives you as much freedom to move as it does support to focus.

Fred Scott was a brilliant designer. He studied at the Royal College of Art in the early ’60s and it is a shame that his talent is not more broadly recognised. I regret that I never met him.

I have worn Wallabees since I was at college in Newcastle in the ’80s. They somehow seem to exist outside of time and fashion.

I wear them pretty much all the time — with suits or with sweatpants.

They are supremely comfortable, which is important, as I have challengingly wide feet.

I have been obsessed with shoemaking for years and have had formal shoes made by the remarkable George Cleverley in The Royal Arcade. Shoes are a wonderfully ancient and fascinating product category that recently was profoundly disrupted by the sneaker. Trainers feel like SUVs to me. The innovation and functionality provide benefits even if you don’t exploit their total capability.

Wallabees have the functional advantages of trainers, but they are still shoes. They are the original Land Rover Defender, rather than a contemporary SUV.

I love the suede, the crepe sole and moccasin stitching. I love that you understand how they are made. I love that they have the perfect number of lace holes. Wallabees are perfect.

Timekeeping is surely a forgivable obsession. I have become increasingly fascinated by the technology and the products that have been developed to keep time. This fascination culminated in our work on Apple Watch.

While I like examples from all timekeeping product categories, I have a particular affection for a longcase clock that I have in the hallway of our home in San Francisco.

Beyond how beautifully it was made, and its exceptional timekeeping, this grandfather clock has a comforting place in the house that is hard to articulate. Perhaps it is the anthropomorphic size and proportion, or perhaps the gorgeous tick-tock and hourly chime. This clock has a calm and otherworldly presence that I adore.

The technologies of timekeeping have defined cultures and societies. The gentleness and humanity of this clock’s design belies those unimaginably powerful technologies.

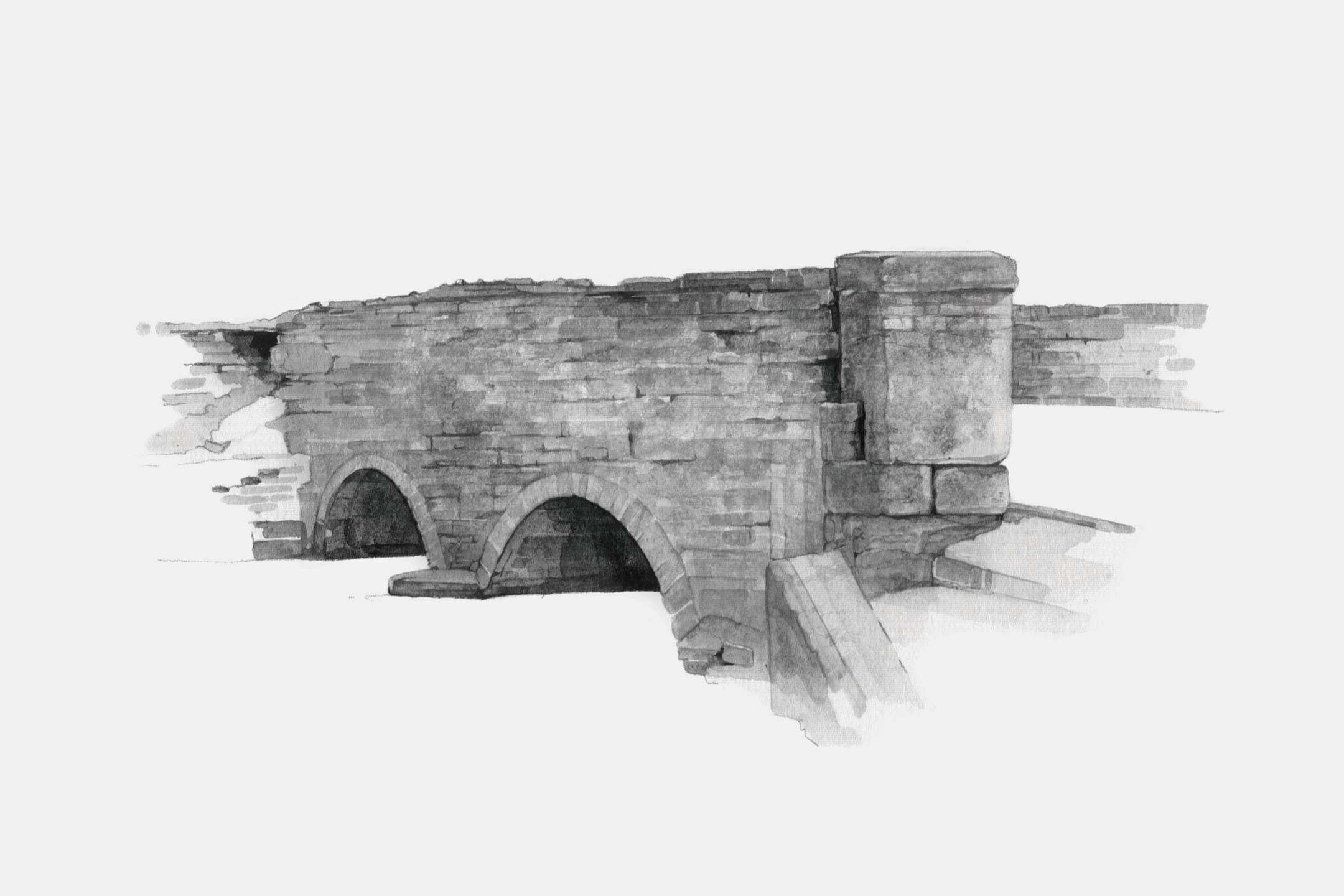

Bridges seem to exist in a design and architectural category uniquely their own. Their ambiguity as structures or buildings or products is curiously at odds with how singular and distinct their symbolism and function. If I could pursue the focused study of just one area over the coming years, bridges would be a strong contender.

While they serve a clear and understandable purpose, their gravitas, their call to attention, seems compelling, fundamental, almost primal.

There are only a few bridges that I do not like and there are many that leave me speechless.

While magnificent, ambitious and tenacious bridges can define cities and entire regions, I also find the simple, modest stone bridges of the Cotswolds equally compelling. There is a small bridge that crosses the River Coln at Ablington that is integrated into the adjacent dry stone walls that I truly love.

Whether sitting on it at the end of a hot day in June, or walking along the river and catching glimpses of it through the willow, I find it utterly complete and reassuringly beautiful.