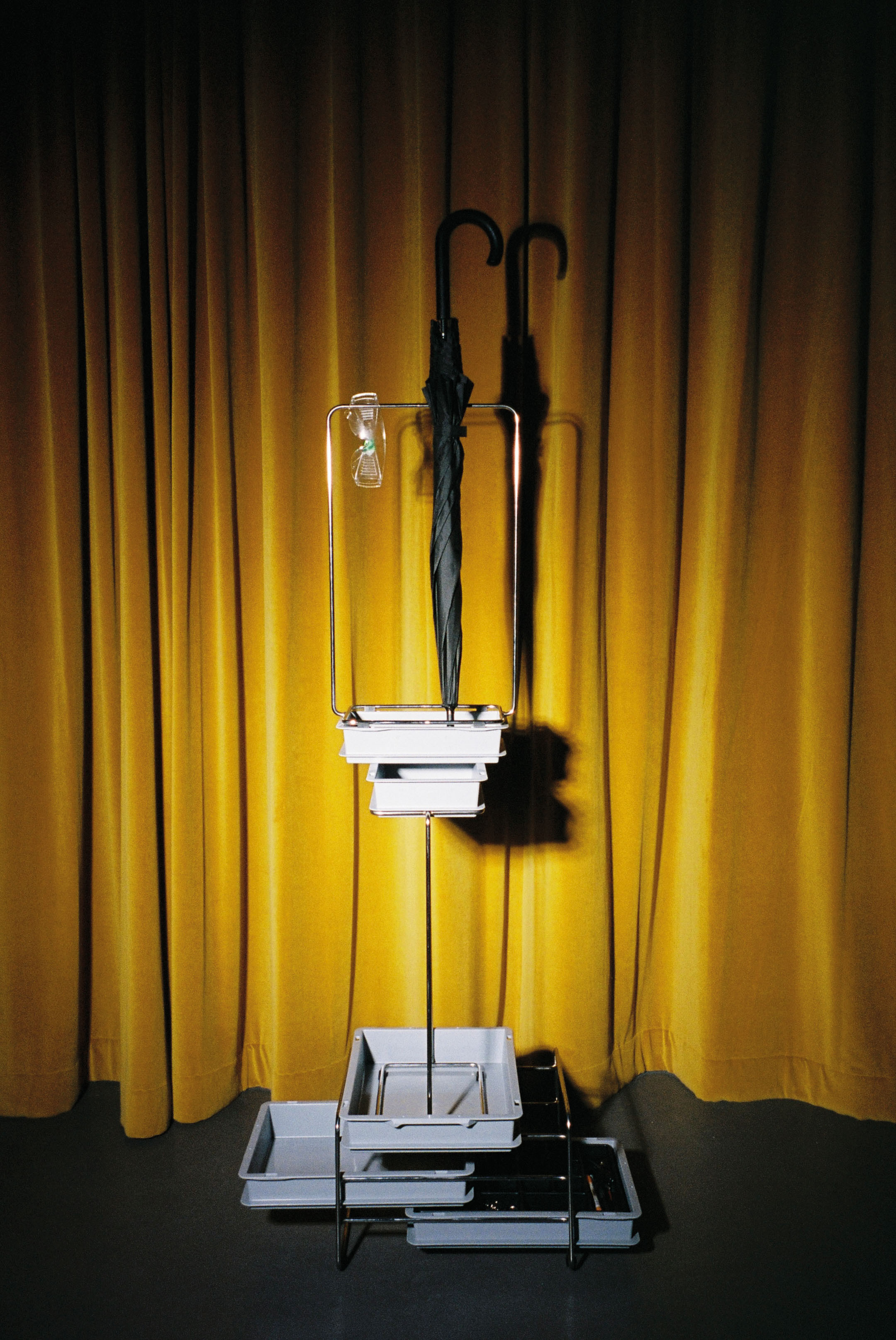

Rako hack storage system

The Georg Utz group is a manufacturer of storage containers including the Rako range. Hilfenhaus transformed a generic industrial plastic product into a domestic system.

Design Justus Hilfenhaus, photography Isabella Madrid

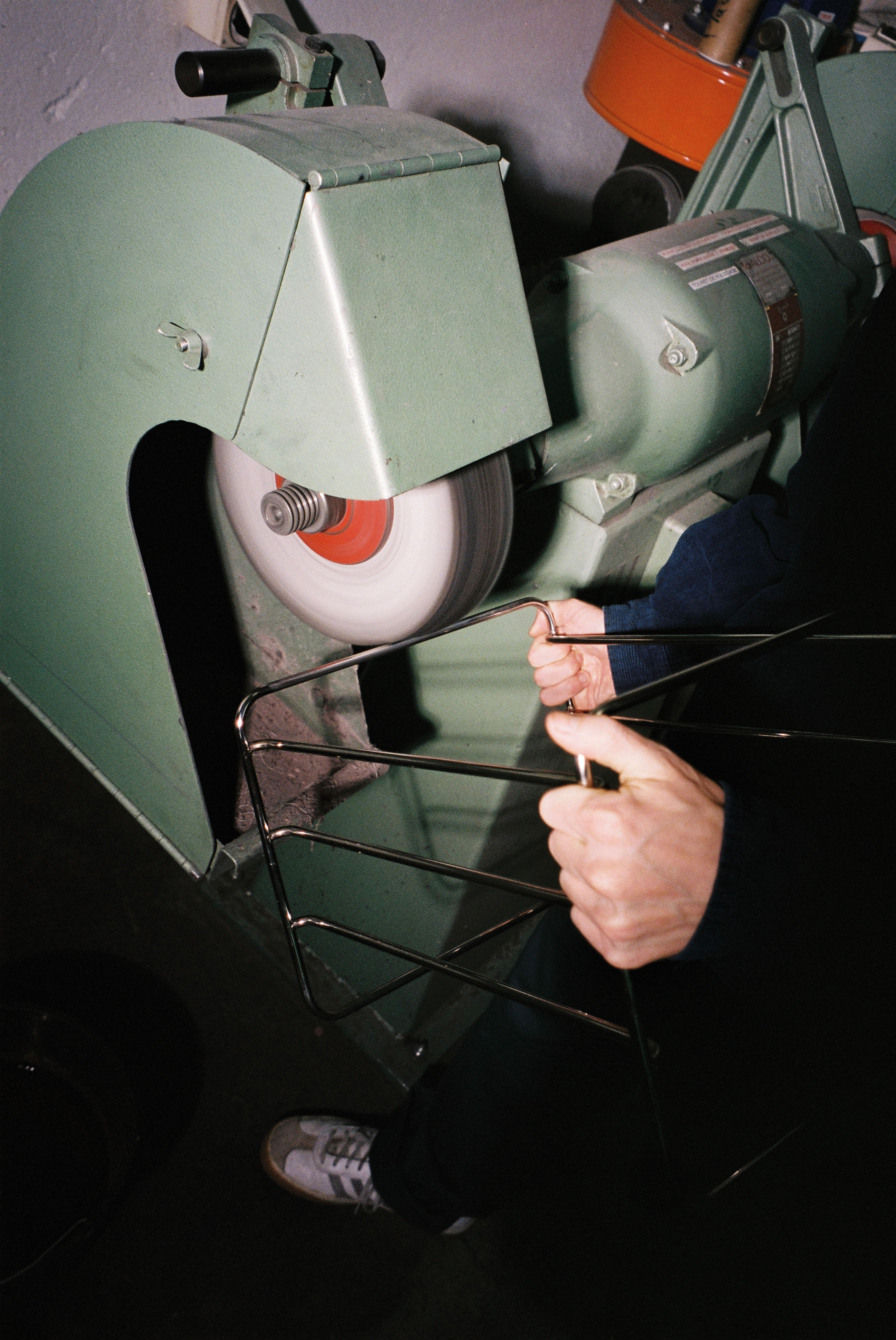

Caddie basket

Caddie is a French-owned company that has been manufacturing supermarket trollies since 1957 using wire-working techniques. Caddie has a robotised production line. Weber used ECAL’s work- shops to weld her own version.

Design Loïs Weber, photography Carla Rossi

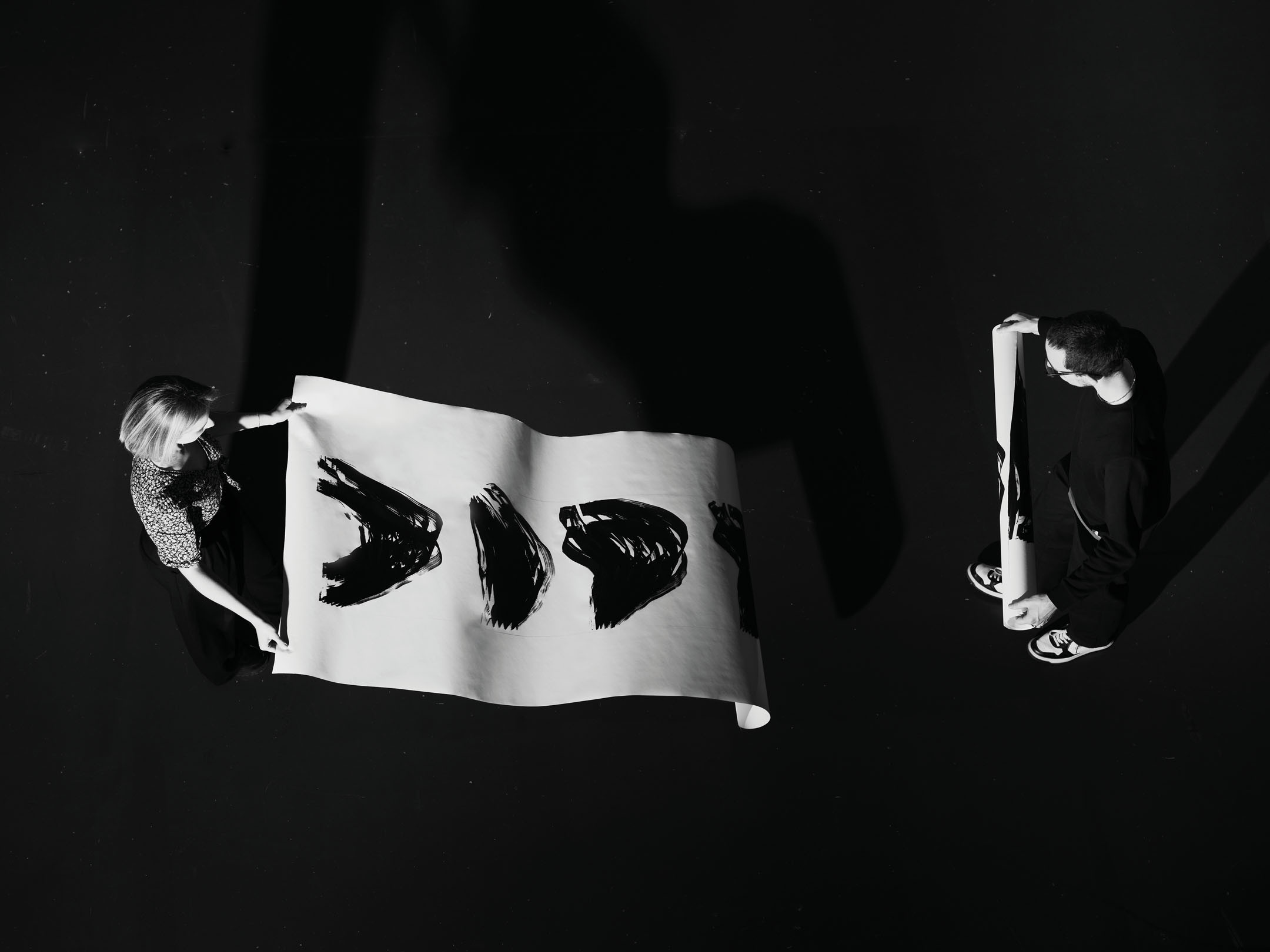

Accordion DIY calligraphy tool

Calligraphy is part of the course for type design master’s students and they were recently asked to design a tool to work with. Product design students, meanwhile, were asked to come up with a design based on an existing brand, and to use its manufacturing techniques and product history to come up with a new design that would fit into its catalogue.

Design Þorgeir Blöndal, Maximillian Inzinger and Anna-Sophia Pohlmann, photography Gina Bolle

Recyclable shoes for children

Rieckhoff worked on a range of children’s shoes that can be manufactured without the use of glue, allow- ing the components to be reused. She explored the idea of a rental system that would allow parents to trade shoes in as their children grow.

Design Yohanna Rieckhoff, photography Benjamin Freedman

Avatar tool

A project exploring the connection between the digital and physical worlds.

Design Luis Shiro Rodriguez, photography Florian Hilt

U.F.O.G.O Site specific wind turbines

Fogo, the Canadian island off the coast of Newfound- land is the subject of a series of social enterprise developments initiated by Zita Cobb, a successful businesswoman who grew up there. She has invested in sustainable projects that aim to maintain life on the island. ECAL’s students worked on the design of wind turbines tailored for the location.

Design Marcus Angerer, Jule Bols, Fleur Federica Chiarito, Matteo Dal Lago, Sebastiano Gallizia, Sophia Götz, Maxine Granzin, Lucas Hosteing, Paula Mühlena, Cedric Oder, Oscar Rainbird-Chill, Yohanna Rieckhoff, Luis Rodriguez, Donghwan Song, Chiara Torterolo, Luca Vernieri, photography Marvin Merkel

Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby, who pioneered a speculative approach to design as professors at the Royal College of Art in London before moving to New York, convinced their students that asking questions is as important as trying to answer them. Their approach was to explore the consequences of fictional scenarios. What would the world be like if the tendencies that we are just beginning to see are extruded to their logical consequences. They used the same method when they turned their attention to the nature of design education.

“Today we visited a new school of design developed specifically to meet the challenges and conditions of the 21st century. It offers only one degree – an MA in constructed realities,” they wrote.

“There are no disciplines in the conventional sense, instead students study bundles of subjects: rhetoric, ethics and critical theory combined with impossible architecture scenario making and world building, mixed with ideology and found realities and CGI and simulation techniques taught alongside the history of propaganda, conspiracy theories, hoaxes and advertising.”

They were clearly teasing the Design Academy Eindhoven which established its reputation by abolishing traditional skills-based definitions of design. Rather than teaching industrial design, or furniture design, graphics or interior design, as design schools once did, just as a previous generation had departments of leather, metal, ceramics, glass, and textiles, it offers programmes in contextual design, social design and design curating. In some ways this is a natural response to the accelerating pace of change triggered by the digital explosion. As the emphasis has shifted from material objects to the immaterial, design education has been reconfigured. Yet the more that world dematerialises, the more that we value tactile, physical qualities and skills.

Of the three design schools in Europe that most often get mentioned as places to watch, The Ecole Cantonale d’art de Lausanne is the most straight-forward and unassuming in the way that it teaches. In Eindhoven, where things have moved on at a pace since Dunne and Raby’s speculations, students now choose between enigmatically named courses in Studio Body Building, Studio Turn Around, The Invisible Studio and The Morning Studio, but in Lausanne, they still have a photography department, a type design department, and a product design department. Perhaps as a result, it is also regarded as the place that turns out the most employable graduates. In some places ‘employability’ is a suspect concept. When Ron Arad taught at the Royal College of Art, he used to suggest that his job was to make his students unemployable. What he was getting at was independence of mind. He wanted his students to be capable of working on their own. When Arad ran the department of design product, its graduates included Martino Gamper, Max Lamb and Paul Cocksedge. While Lausanne doesn’t put it in the same way as Arad did, many of its graduates have gone on to make their own mark too. BIG-GAME, the product design studio founded in 2004 by Augustin Scott de Martinville, Elric Petit and Grégoire Jeanmonod, Carolien Niebling, memorable as the inventor of the sausage of the future, Adrien Rovero, responsible for windows for Hermès, the passionate photographer Karla Hiraldo Voleau, and the typographers Maximage and Omnigroup are all ECAL graduates.

With only around 600 students, Lausanne is also the smallest of the three schools, even though it offers a foundation year, as well as bachelors, masters and research programmes. The Swiss education system is well funded enough for ECAL to be able to charge a fee of just £900 for all students including those from abroad, and for them to work in what other schools would see as tiny groups.

With 1,400 students, London’s Royal College of Art, which was once based only on Masters programmes, is not the place it was when Arad taught there, let alone when David Hockney almost failed to get his diploma. Home students are now charged £8000 a year, or £9,750 if they want a studio space and access to what the RCA calls ‘more than a low level of technical provision’. For overseas students it’s £29,000. As the RCA website warns; “The College reserves the right to charge students the higher fee band if, a student is found to be occupying space and using resources in line with the ‘high residency’ provision.” Aware of the steep cost for its students, the RCA is cutting back its Masters programmes, from two years to just one.