If you position the contemporary throughout one of the world’s great historic houses, what will happen next? My co-curator Alexandra Hodby and I have been wondering this over the past three years, as we put together ‘Mirror Mirror: Reflections on Design at Chatsworth’, in partnership with Friedman Benda gallery. The exhibition, which opened at the renowned country estate in March, is in many respects a dream project. No stage could be grander. Built and maintained by 17 generations of the Cavendish family, Chatsworth has a truly fabulous (there’s no other word for it) collection of art, both fine and decorative. It has been a cross-disciplinary gesamtkunstwerk for four-and-a-half centuries and counting, an ever-accumulating repository of aesthetic and scientific innovation. The property, with its extensive garden and woodland, is visited by upwards of a million people a year.

When intervening into this amazing place, we knew we’d have to be judicious. Imposing as it may be, the building’s fabric requires great care. And whether visitors are coming for the first time or the 50th, they want to see Chatsworth in all its glory. There’s a fine line between enhancing that experience and distracting from it: a conundrum we tried to solve by inviting designers who would be able to meet the house halfway, attuning themselves to its qualities. Ultimately, Alex and I settled on 16 studios, most of which created specially commissioned works for the project.

When we released all this into the house, what did happen? The title of this magazine is a good place to start. It will ring a bell if you’ve ever taken a course in philosophy, as Aristotle’s treatise De Anima (usually translated as ‘On the Soul’) has exerted such pervasive influence. It was Aristotle who codified the distinction between animate beings and inanimate things: put simply, the first have souls, and the latter do not. An object like a chair, for example, does have a form (in Greek, eidos), imposed upon it by its maker. But it is not émpsychos (“ensouled”). This implies a hierarchy of existence, which finds direct correspondence in ethics. We have no regard at all for the rights or feelings of objects, very little for houseplants, a bit more for animals. Most of our moral concern is reserved for people, who are not just ensouled, but bestowed with intellect, the ability to reason.

These assumptions are so familiar that we don’t usually even stop to think about them. But they are also very culturally specific. Globally, the majority view held by humankind is that objects can, indeed, have life-force and subjectivity. This is one definition of the sacred, and it is a conviction that is widely shared, across such otherwise dissimilar belief systems as Japanese Shinto, the Yorùbá Ìṣẹ̀ṣẹ religion, Native American cosmologies, and Christianity, with its cult of relics.

Euro-American philosophers, too, have recently offered compelling alternatives to the Aristotelian tradition. Graham Harman’s ‘object-oriented ontology’ and the ‘actor-network theory’ formulated by the late Bruno Latour both seek to emphasise the action that objects exert on the world around them. Jane Bennett’s book Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, similarly, looks both at the ‘recalcitrant’ aspects of objects and their generative potential, the way they can impede or empower.

None of this, however, necessarily implies that ‘inanimate’ things do have souls. One can dispense with that idea, and belief in a divine masterplan, while still thinking of everything, humans included, as existing within an interdependent matrix. As Bennett puts it, maybe a human being is just “a particularly rich and complex collection of materials”. This way of thinking feels increasingly compelling in an era of climate change, which has shown us the perils of a human-centric worldview. Perhaps we’d be better off if we gave everything on earth our ethical consideration: humans, animals, plants, and objects, all in it together.

In ‘Mirror Mirror’, these rather abstract considerations become quite tangible. All across the exhibition, visitors encounter wild things, exploring their new habitats. Fernando Laposse’s ‘Agave Cabinet’, with its shaggy pelt of sisal fiber, seems almost to scent the air. Najla El Zein’s ‘Seduction, Pair 06’ – carved in blush-pink Iranian red travertine, the form obliquely suggests two lovers in what she describes as “timid, yet affectionate, proximity” – sits in the Chatsworth garden, a quietly provocative addition to the statuary on the grounds.

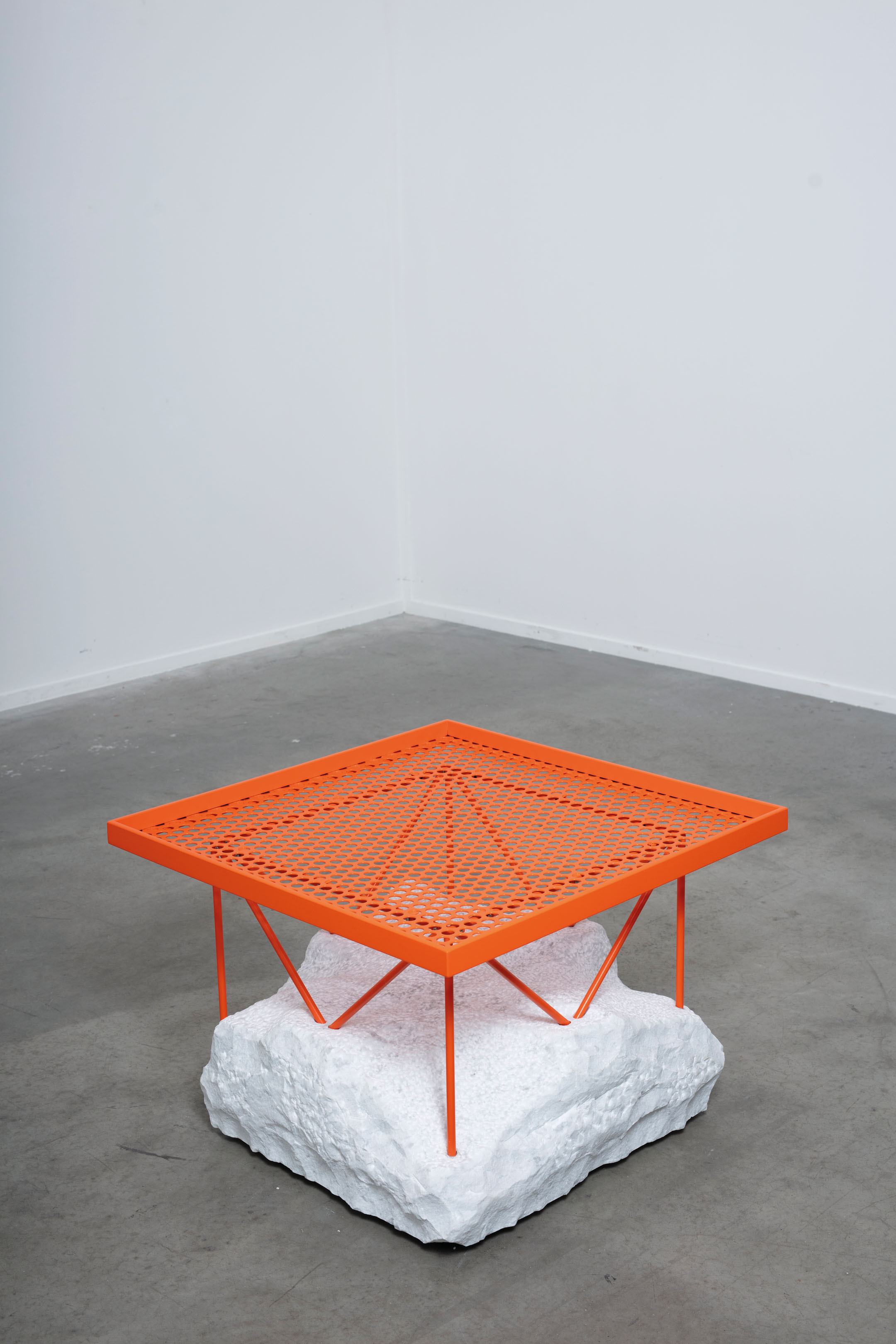

Designs by Samuel Ross, executed in an industrial-classical palette of marble and steel painted in his signature ‘Volt Orange’, land in the house’s sculpture gallery with explosive force, instigating a cross-generational conversation about embodiment, identity, and material exploitation. In an adjoining space hangs Ini Archibong’s ‘Dark Vernus’ chandelier, spectacular and saturnine, accompanied by a soundtrack of beats and voices, composed by the designer himself. Ross and Archibong both invoke the energies of the African diaspora, a philosophical tradition in which object-animacy plays an important role. It’s also salient that both operate in other spheres: Ross made his name as a streetwear designer, and is now gaining attention for his sculpture, while Archibong is an industrial designer working with brands like Hermès, Knoll, and Sé. They arguably provide the most expansive moments in ‘Mirror Mirror’, gesturing to new frameworks of relevance that are just beginning to take shape.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, contemporary objects draw out certain latent qualities in the existing furnishings, making them look fresh again. Ndidi Ekubia’s silver vessels, with their aqueous patterns, remind you of the malleability of all the house’s metalwork, which was either cast from liquid metal or hand-hammered into being. Max Lamb’s ‘6 x 8’ chairs are each bandsawn from a beam of cedar, six-by-eight inches in cross section, with no wastage. This back-to-basics approach throws into high relief the astonishing quality of the 18th-century carving all around them. For one of Chatsworth’s state apartments, decorated with musical symbolism, Jay Sae Jung Oh has made a throne out of used instruments, including a French horn and an electric guitar, wrapping these found objects with narrow cord so that only their shapes can be seen. It’s a fitting addition to a room that’s all about music, but always silent.

The exhibition’s title was meant to anticipate such correspondences. We wanted to emphasise the way that present and past reflect one another at Chatsworth, sometimes even merging into a single image, as when you glimpse yourself in one of the period mirrors with its faded silvering – in a looking-glass darkly, as it were. And to a degree, our project is only the latest contribution to an evolving genre. Contemporary interventions into historic properties (albeit not usually at this scale) have become a regular thing. This is especially true in the UK, where the heritage sector has been extremely proactive in keeping its institutional offer current, and connecting with a broader, inquisitive public.

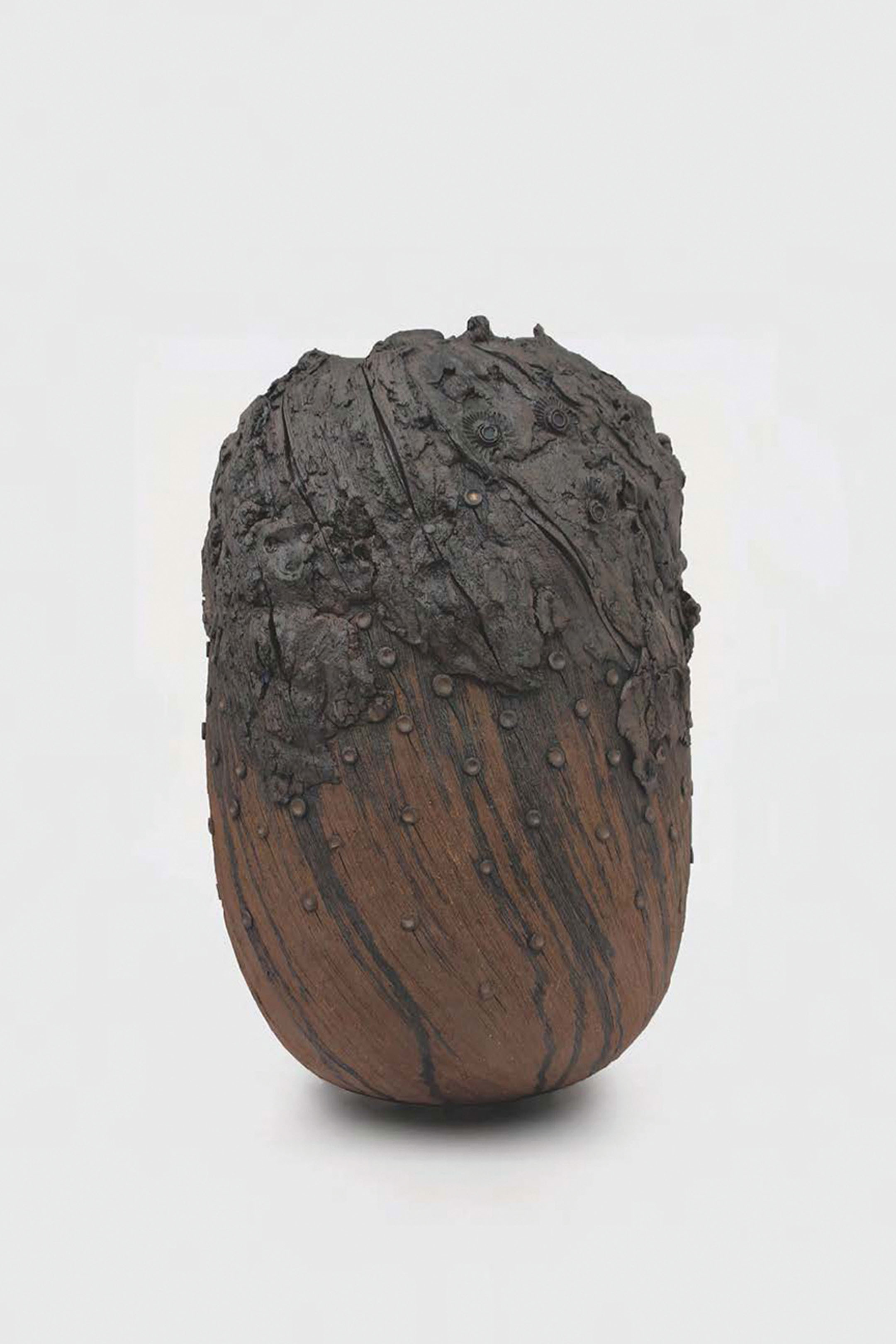

We certainly had these motivations too, but ‘Mirror Mirror’ is also unusual in a couple of respects. First, the project is not a simple encounter between static past and dynamic present. It’s more like a minor key change within an evolving composition. At Chatsworth, there is already design in profusion, brought to the house over many centuries, and our exhibition is a continuation of that ongoing process. We have featured, for instance, several works by the Irish master of bentwood furniture, Joseph Walsh, which were already here, commissioned by the Devonshire family over the past few years. The house is also graced by several contemporary ceramic installations – by Natasha Daintry and Edmund de Waal, among others – and to these we added a suite of torqued, seismic forms by the South African ceramic artist Andile Dyalvane.

A second difference between ‘Mirror Mirror’ and other, apparently similar interventions has to do with the nature of contemporary design itself. The works that we have introduced into Chatsworth are all of domestic scale, and mostly occupy familiar useful typologies (chair, table, vessel). At the same time, they are not the sort of things that people normally encounter in their daily lives: they’re far more intensely made, and freighted with psychological, narrative, or thematic content. In short, these things are design, but of a special kind, in which the condition of design itself is turned to the purposes of self-expression and social commentary, rather than product shaping or problem solving.

In ‘Mirror Mirror’, we acknowledge two well-known progenitors of this approach, Wendell Castle and Ettore Sottsass. Both opened their minds to new possibilities in the late 1950s, way ahead of the curve, and pursued their own restless curiosity for decades thereafter, seemingly wherever it would lead. It’s telling that both remained devoted to the genre of furniture, and other functional things. That left them plenty of room to explore, while also providing the friction needed to spark their creativity.

In the show, Castle is represented by three cast-bronze settees, out in the Chatsworth garden, and Sottsass by monumental glass vases, distinguished by their polychrome palette and elaborate hanging appendages. It’s common, but ultimately somewhat misleading, to analogise such fantastic objects to fine art. The impulse is understandable. The design they pioneered is highly individualistic and formally inventive, just as we expect painting and sculpture to be. And calling anything art, in our society, is a way of elevating it (arguably itself an aspect of Aristotelian ontological hierarchy, in that art is construed as one of the highest expressions of the human intellect). But there’s also an important difference, in that design, however creative and innovative, exists within the register of everyday objecthood. That’s what makes it design.

This potential renders ‘Mirror Mirror’ a case study in the behaviour of objects, specifically when they are introduced into a potent space, and allowed to engage with its innate qualities. The sense of place at Chatsworth – what the ancients would have called its genius loci – exists in a certain tension with the objects we’ve introduced. The building’s façades, completed in around 1700 by the First Duke of Devonshire to designs by William Talman and Thomas Archer, are a study in Italianate neoclassicism. Archer also contributed a baroque ‘temple’, which stands atop a majestic stepped cascade in the garden. It’s one of several features on the grounds that astonishes for its sheer engineering prowess – another being the system of tunnels and fountains that Joseph Paxton created in the 1830s and ’40s. Sadly, his most spectacular contribution to Chatsworth, a coal-heated glass and steel arboretum that anticipated his famed Crystal Palace for the 1851 Great Exhibition, was dismantled in 1920, leaving only its impressive foundations.

This deep background, equal parts academic architecture and technical infrastructure, makes the imaginative individualism of the contemporary design in ‘Mirror Mirror’ all the more striking. The crystalline furniture of Detroit-based maker Chris Schanck – known for his signature ‘Alufoil’ technique, in which scrap assemblages are encased in a gleaming carapace of foil and resin – is set in Chatsworth’s ‘grotto’, an intimate room with a subterranean vibe. (It was installed with running water in 1692, when indoor plumbing was an almost unheard-of novelty.) The setting certainly feels right for the objects, but there’s also an obvious incongruity – as if pieces of a sci-fi film set, or perhaps Superman’s Fortress of Solitude, had been teleported into the space. Similarly, Michael Anastassiades’ bamboo lighting cuts an elegant but arresting figure in Chatsworth’s library. The gentle illumination is appropriate to the space, with its profusion of antique leather bindings, but the installation also recalls the sculptures of Dan Flavin (particularly his ‘Monuments’ to Vladimir Tatlin), echoing their decisive and austere minimalism.

We invited Faye Toogood to respond to Chatsworth’s spectacular chapel – the least altered of the house’s 17th-century spaces, now decommissioned for religious use, but still plenty resonant. She created a set of benches and tables in so-called ‘Purbeck marble’ – actually a kind of limestone, quarried in Dorset, in which dense deposits of snail shell are captured, a good example of a material that asserts its own claim to meaning. Toogood has also provided seating so that visitors can sit and reflect. The arrangement recalls Neolithic standing stones and circles, invoking a continuum of spirituality extending far back into history; it makes the baroque chapel seem relatively modern in comparison.

In all these cases – and throughout ‘Mirror Mirror’ – the designs that we introduced do indeed exhibit a profound subjectivity, or something very much like it. Nothing is inert. Fortunately, Chatsworth can take it: far from being disrupted or interfered with, the house seems more like itself than ever. This hybridisation of worlds is what design can do, like nothing else can.

A final contribution to ‘Mirror Mirror’ exemplifies this principle: Joris Laarman’s triad of ‘Symbio Benches’. Hand-carved from boulders from Chatsworth’s own quarry, the pieces have recessed channels cut into them, which are lined with a ‘bio-receptive’ phosphate-rich cement. This encourages growth by providing water retention and frost resistance, as well as elementary fertiliser. The pieces complete themselves as they sit there, interacting with their surroundings. Mosses and lichens slowly but surely populate the carved recesses, filling out a graphic image that traverses their shapes. Rather than keeping nature at a safe distance, as industrial design tends to do, here it is welcomed and nurtured. It becomes a creative partner.

Laarman’s works are unusual specimens, in that their surfaces are literally, as well as figuratively, alive. And Chatsworth is admittedly an extreme setting, an unusually fertile landscape for design. Yet ‘Mirror Mirror’ is, ultimately, an expression of what is evolving in the field today. Design’s most adventurous practitioners are operating outside the imperatives of mass production, using that hard-won freedom to make objects of supremely individualistic character. These objects, in turn, make their own way in the world, animating whatever circumstances in which they find themselves. Does this mean that they, themselves, possess anima? It’s hard to see what we gain by denying it.

‘Mirror Mirror: Reflections on Design at Chatsworth’ runs until 1st October 2023